ADHD, new research

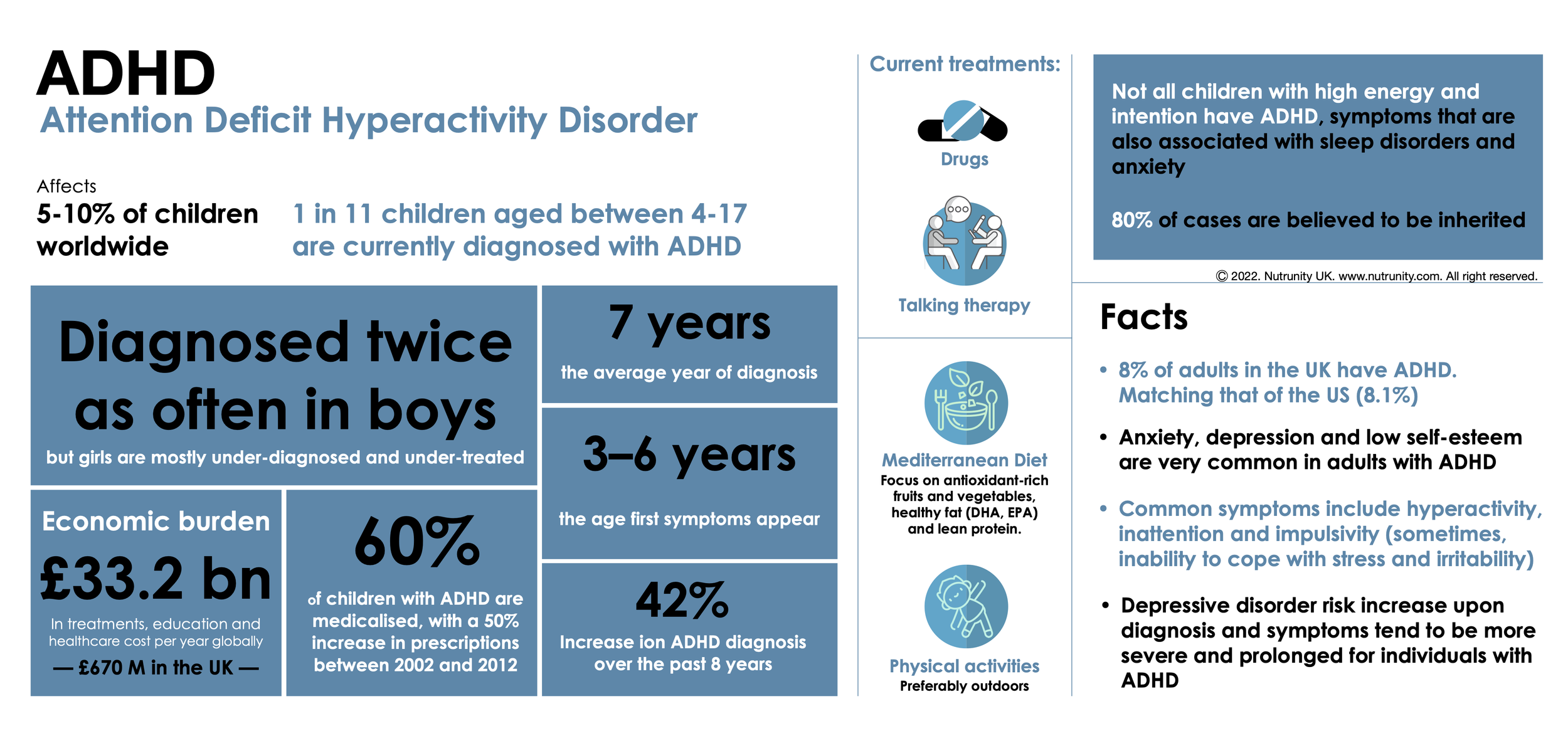

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), is one of the most prevalent mental disorders in children, a condition that interferes with functioning or development and can lead to learning impairment — often lasting into adulthood.

ADHD is diagnosed approximately twice as often in boys than in girls, but it is also believed that it is very often undiagnosed in girls.

What is ADHD?

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is a neurodevelopmental disorder (developmental impairment of the brain’s executive functions) characterised by excessive levels of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity.

Common Symptoms of ADHD

ADHD symptoms vary from individual to individual. You or your child may experience all or a only few of the above symptoms below:

Lack of focus (or hyperfocus — may be able to maintain an unusually prolonged and intense level of attention for tasks they do find interesting or rewarding)

Inattention (short attention span, trouble concentrating)

Hyperactivity, constantly fidgeting (being restless)

Poor time management skills

Problems prioritising

Trouble multitasking

Inability to cope with stress

Problems following through and completing tasks

Impulsivity (acting without thinking), and/or

Exaggerated emotions (frequent mood swings)

ADHD may be identified or diagnosed later in life, even though symptoms

started during childhood. Some adults continue to have major symptoms that interfere with daily functioning and often struggle with impulsiveness, restlessness and difficulty paying attention, while hyperactivity is no longer as predominant.

Adult ADHD can lead to unstable relationships, poor work/school performance, low self-esteem, and many other problems.

Types of ADHD

Primarily hyperactive-impulsive type — The individual is often impulsive, impatient, and interrupts others (lack of social cues).

Primarily inattentive type — The individual is easily distracted and forgetful and may have difficulty focusing, finishing tasks, and following instructions, often daydreamers, easily losing track of time.

Primarily combined type — The individual displays a mixture of all the symptoms given above (to be diagnosed, they must exhibit 6 of the 9 symptoms identified for each sub-type).[1]

Differential diagnosis

There is no single test to diagnose ADHD. Many of the symptoms may also occur as a result of sleep disorders, anxiety, depression, and certain types of learning disabilities, and, therefore, it is important to rule out other conditions and have a discussion with the individual as to what may be the problem or their inadequacies.

Conventional treatment

According to NHS UK, ADHD can be treated using medicine (taken daily or on certain days, like schooldays) or therapy (CBT, particularly for Adult ADHD), but a combination of both is often recommended.[2,3]

Naturopathic approach

Looking at the whole person, evaluating the role of nutrition (particularly malnutrition due to diet, stress and gut inflammation/dysbiosis) and other factors (including food sensitivities and allergies, toxic load and sleep problems) are key to restoring balance and reducing the severity of symptoms.

1. Diet

Diet plays a key role in brain function and many essential nutrients are implicated in proper functioning. A diet lacking those nutrients may be implicated in dysfunction and the severity of symptoms. Having a direct impact on digestive capabilities, stress can lead to malnutrition and gut inflammation. Inflammation may be further exacerbated by food hypersensitivities (intolerances) and lead to increased intestinal permeability.

Following an elimination diet may be a priority as to avoid the foods responsible for hyperactivity and distraction, including blood sugar management. You may want to test for food hypersensitivities. Following a Mediterranean Diet, rich in plant foods, particularly pigment-rich fruits and vegetables, nuts, legumes, and extra virgin olive oil (and fat-rich foods such as oily fish, linseeds and other plant sources). A diet focusing on healthy fats and protein, as well as dietary fibre, is also key to regulating blood sugar.

Additionally, improving sleep may play a role in managing symptoms. Children and young adults with ADHD (or any other condition worsen by a lack of sleep) should not keep their smartphones in the bedroom, as it can lead to sleep disorders, increased anxiety and social inadequacy, as well as online bullying and upset.

Physical exercise and time spent outdoors in nature tend to benefit children with ADHD.

2. Supplementation

Malnutrition and deficiencies have been implicated in ADHD, particularly magnesium, iron, omega-3 fatty acids and vitamin D. Research also shows a connection between B vitamins and the severity of symptoms. A large number of studies shows that supplementing with (therapeutic dosage of) fish oil can improve symptoms. As so does a gut healing protocol (gut dysbiosis is associated with cognitive dysfunction).

Herbal remedies are also shown to be useful, particularly in calming the nervous system and addressing restlessness, anxiety and irritability associated with the condition.

A new study (a 10-week, randomised, double-blind, placebo and active treatment controlled multicentre trial) from the University of Antwerp shows promising results with the use of pycnogenol in a targeted protocol. Pycnogenol is a special extract from the bark of the French maritime pine.

For the study, researchers divided 88 children into three groups over a ten-week period and gave them either pycnogenol (based on the children's weight, ranging from 20-40 mg per day), methylphenidate or a placebo. The study also included questionnaires from teachers involved and the parents (completed at baseline and after five and ten weeks), including the ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD-RS), which measures nine criteria for inattention and nine for hyperactivity/impulsivity[1], as well as immunity, oxidative stress, serum zinc and other markers.

At the end of the study, children taking pycnogenol showed a decrease in the ADHD total rating scale and a decrease in hyperactivity/impulsivity and a decrease in inattention. An improvement in these parameters could also be seen in those children who were given the drug, but they suffered five times more adverse side effects (including arrhythmia) compared to those children in the pycnogenol group.[4] The findings contradict many previous studies, based on very small numbers of participants (e.g., as published in the same journal in 2002).

Furthermore, a meta-analysis (including 81 unique trials) reported that “overall, despite a class effect of improving clinical response relative to placebo, there were few differences among the individual ADHD pharmacotherapies, and most studies were at risk of at least one important source of bias. Furthermore, the certainty of the evidence was very low to low for all outcomes, and there was limited reporting of long-term adverse events.”[5]

“Most studies were at risk of at least one important source of bias [...] and there was limited reporting of long-term adverse events”

It has also been evaluated that EPA and DHA, essential omega-3 fatty acids, should be considered an adjunct to any protocol.

Supplementation with magnesium and vitamin B6 led to a significant reduction of clinical symptoms, such as hyperexcitability, aggressiveness and attention deficits, after two months in almost all children in a trial series.

Numerous neurochemical metabolic processes are zinc-dependent and studies have shown that low zinc levels are repeatedly reported in children with ADHD. In studies, zinc supplementation led to a reduction in hyperactivity, impulsivity and disturbed social behaviour.

Coenzyme Q10 is a central factor in mitochondrial energy production and display strong antioxidant properties and can effectively prevent radical-induced damage to the nervous system, such as that caused by heavy metals. Polyphenols, such as those found in grape seed extract, appear to play a similar role.

Research demonstrates that individuals with ADHD could benefit from vitamin B12 adequate intake/supplementation. Vitamin B12 is involved in the methylation of myelin, neurotransmitters and phospholipids. Deficiency has been linked to neuropsychiatric symptoms such as memory/concentration disorders or depressive moods.

Blood testing for vitamin and mineral concentrations can be used to identify deficiencies or imbalances. Testing for fatty acid levels and ratio of omega-3s and omega-6s may also be essential.

Pycnogenol

Hippocrates used pine bark for the treatment of inflammatory diseases and, therefore, there was already an understanding of the virtue of the compounds found in pine bark.

The key constituents of pycnogenol include proanthocyanidins (polyphenols), bioflavonoids and organic acids with natural active properties.[6]

There are over 130 clinical studies and more than 300 scientific publications have been made about pine bark extract and its benefits on human health.

Other benefits of pine bark:

Antioxidant properties — helps with 1) the regeneration of vitamin C, vitamin E and glutathione, 2) increase in antioxidative capacity, and, 3) the inhibition of lipid peroxidation.

Inflammation — modulates proinflammatory cytokine function.

Pain — inhibits enzymatic function, such as cyclooxygenase (COX) 1 and 2, and maybe a useful adjunct to PMS and endometriosis protocols.[7-14]

Asthma, allergies and immunity — reduces the release of histamine and stimulates the immune system, and reduce leukotriene levels and associated bronchoconstriction.[15,16]

Cardiovascular support — demonstrates antithrombotic (inhibits platelet aggregation) and vasolidaltive (increases endothelial nitric oxide bioavailability) effects, and improves microcirculation.

Resolution of diabetes complications by increasing capillary blood flow — improved capillary filtration and oedema reduction[17], faster healing of diabetic ulcers[18], and prevented progression of existing retinopathy.[19] It may also reduce carbohydrate absorption and, therefore, blood glucose levels by inhibiting duodenal alpha-glucosidase.[20]

Plays an important role in stabilising and maintaining connective tissue functions and can be added to the treatment of haemorrhoids.

References

CDC. (2022). Symptoms and Diagnosis of ADHD. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/diagnosis.html

NHS. (). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) - Treatment. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd/treatment

Van der Oord, S. et al. (2020). A randomized controlled study of a cognitive behavioral Planning intervention for college students with ADHD: An effectiveness study in student counseling services in Flanders. Journal of attention disorders. 24(6), pp. 849-862. doi:10.1177/1087054718787033

Verlaet, AA. et al. (2017). . Effect of Pycnogenol® on attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 18(1), 145. doi:10.1186/s13063-017-1879-6

Elliott, J. et al. (2020). Pharmacologic treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS One. 15(10), e0240584. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0240584

Pandey, KB. Rizvi, SI. (2009). Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2(5), pp. 270-278. doi:10.4161/oxim.2.5.9498

Schäfer, A. et al. (2005). Inhibition of COX-1 and COX-2 activity by plasma of human volunteers after ingestion of French maritime pine bark extract (Pycnogenol®). Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 60, pp. 5–9.

Grimm, T. et al. (2006). Inhibition of NF-kappaB activation and MMP-9 secretion by plasma of human volunteers after ingestion of maritime pine bark extract (Pycnogenol®). Journal of Inflammation Research. 3, pp. 1-6.

Belcaro, G. et al. (2008). Variations in C-reactive protein, plasma free radicals and fibrinogen values in patients with osteoarthritis treated with Pycnogenol®. Redox Reports. 13, pp. 271-276.

Cisar, P. et al. (2008). Effect of pine bark extract (Pycnogenol®) on symptoms of knee osteoarthritis. Phytotherapy Research. 22, pp. 1087–1092.

Belcaro G. et al. (2008). Treatment of osteoarthritis with Pycnogenol®. The SVOS (San Valentino Osteo-Arthrosis Study). Evaluation of signs, symptoms, physical performance and vascular aspects. Phytotherapy Research. 22, pp. 518-523.

Suzuki, N. et al. (2007). Effect of Pycnogenol®, French maritime pine bark extract, on dysmenorrhea: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 53(5), pp. 338-346.

Maia, H. Jr. Haddad, C. Casoy, J. (2013). Combining oral contraceptives with a natural nuclear factor-kappa B inhibitor for the treatment of endometriosis-related pain. International Journal of Women's Health. 35. 6, pp. 35-39. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S55210

Trebatická, J. et al. (2006). Treatment of ADHD with French maritime pine bark extract, Pycnogenol. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 15(6), pp. 329-335.

Sharma, SC. et al. (2003). Pycnogenol® inhibits the release of histamine from mast cells. Phytotherapy Research. 17, pp. 66–69.

Hosseini, S. et al. (2001). Pycnogenol® in the management of asthma. Journal of Medicinal Food. 4, pp. 201–209.

Cesarone, MR. et al. (2006). Rapid relief of signs/symptoms in chronic venous microangiopathy with pycnogenol: A prospective, controlled study. Angiology. 57(5), pp. 569-576.

Belcaro, G. et al. (2006). Diabetic ulcers: microcirculatory improvement and faster healing with Pycnogenol®. Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis. 12, pp. 318–323

Schönlau, F. Rohdewald, P. (2002). Pycnogenol® for diabetic retinopathy. A review. International Ophthalmology. 24, pp. 161–171.

Schäfer, A. Högger, P. (2007). Oligomeric procyanidins of French maritime pine bark extract (Pycnogenol®) effectively inhibit alpha-glucosidase. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 77, pp. 41–46.