HUMAN PAPILLOMAVIRUS (HPV)

IMPORTANT FACTS

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is a group of viruses that are extremely common worldwide.

There are more than 100 types of HPV.

14 types are known to be cancer-causing (also known as high-risk types).

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI), with over 40 types being passed through skin-on-skin contact. It can affect the genital areas, mouth or throat.

In most cases, the body’s immune system is able to fight infection before it progresses into genital warts.

Cervical cancer can be caused by sexually acquired infection with HPV, the fourth most common cancer amongst women aged 15–34 years old. There were an estimated 570,000 new cases in 2018 worldwide, and nearly 300,000 associated deaths that year,

Cervical cancer can take more than 20 years to develop after infection.

Typically, a person may not notice symptoms.

In the US alone, 1 person gets cancer caused by HPV every 12 minutes (43,371 yearly).

Cervical cancer can be cured if diagnosed in the earlier stages and treated promptly.

Two types of HPV (16 and 18) cause about 70% of cervical cancers and pre-cancerous cervical lesions. Vaccines have been approved for use in many countries to protect against these two types of HPV. Approximately 4% of all cancers are associated with HPV.

WHAT IS HPV?

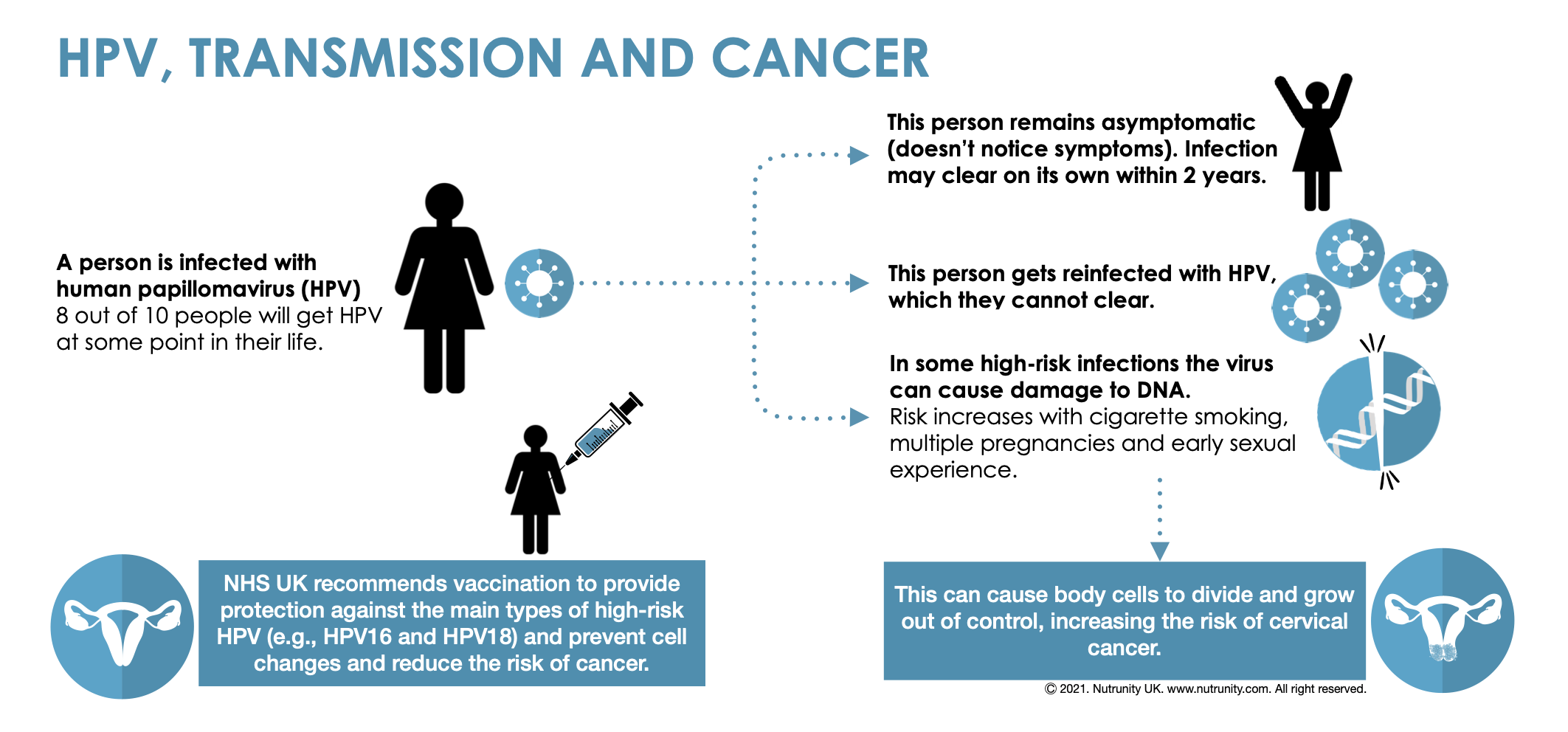

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common viral infection of the reproductive tract, affecting sexually-active men and women. Many individuals may be repeatedly infected. It is often contracted shortly after becoming sexually active, although the main point of transmission is skin-on-skin contact.

There are many types of HPV. While many do not cause problems (individuals may remain asymptomatic — do not experience any symptoms, and infection often clears up within a few months without any intervention), a small proportion of infections with certain types of HPV can persist and progress to cervical cancer.

Nearly all cases of cervical cancer can be attributable to HPV infection.

Non-cancer causing types of HPV (e.g., type 6 and 11) can, however, cause genital warts and respiratory papillomatosis (tumours growing inside the air passages of the respiratory tract). Genital warts are very common and highly infectious, often affecting one’s sexual life.

RISK FACTORS

People who are immunocompromised, such as those living with HIV, are more likely to have persistent HPV infections. HPV infections are also common amongst other sexually transmitted agents (e.g., herpes simplex, chlamydia and gonorrhoea).

It is important to remember that re-infections are highly common, and so the severity of the infection and associated symptoms are highly-dependent on the state of immune defences at the time. The immune system is often struggling to keep up during times of heightened stress, either due to lower nutrient intake (e.g., malnutrition, crash-dieting, strict calorie-restrictive diets, excessive intake of ultra-processed and nutrient-poor foodstuff), chronic stress (including anxiety and depression), tobacco smoking, excessive alcohol intake, and infections (e.g., colds and flu). This increases the risk of infection, persistent infections and cervical cancer.

According to the World Health Organisation, it takes 15 to 20 years for cervical cancer to develop in women with normal immune system. It can take only 5 to 10 years in women with weakened immune systems.

“It is important to remember that re-infections are highly common, and so the severity of the infection and associated symptoms are highly-dependent on the state of immune defences at the time.”

A COMPREHENSIVE APPROACH

The most important component to fight infections is a robust immune system. Therefore, it makes sense to promote a healthy immune response and give the body all it needs to fight infections and promote nutrient assimilation and utilisation.

In addition, a healthy gut milieu is necessary to establish robust immune responses; the first line of defence against the external environment. This may not protect from skin-on-skin infections, yet it is important to look after your gut to maximise digestive capabilities and absorption of nutrients.

For a proper functioning of the body, a strong immune system and antioxidant defences, a wide array of nutrient are required, many of which act as cofactors. In case of antioxidant enzymes, these cofactors may include the coenzyme Q10, vitamins B1 and B2, carnitine, selenium, and often transition metals copper, manganese, iron, and zinc. Deficiencies in the diet will, therefore, have a direct effect on immune defences, as well as enzymatic antioxidant capabilities (naturally-produced to prevent free radical damage). Glutathione and superoxide dismutase offer antioxidant defences. They may, however, become overwhelmed and insufficient due to an inflammatory diet, chronic chemical exposure (e.g., toxicants) and dysbiosis (unbalanced gut microbiome), which may lead to increased gut permeability and widespread inflammation.

To prevent infections, it is always recommended to nourish the body with a wide range of deeply-coloured fruits and vegetables. Think rainbow. Try to consume one portion of each every day, organic if possible, to provide an ongoing supply of nutrients with antioxidant activity. Organic lean meat and small fatty fish are also recommended, about one to two portions a week.

It is also currently recommended by the NHS that girls aged 9–14 years be vaccinated before they become sexually active. Different vaccines may offer protection against different types of HPV. Even ‘perfectly healthy’ women over 30 years old who are sexually active should be screened for abnormal cervical cells and pre-cancerous lesions.

A NATURAL APPROACH

Supplements can support the body in many ways, especially when deficiencies are confirmed. Supplements can have a decisive effect in supporting the immune system and warding off any infection.

Once infected and diagnosed, it may be possible to support conventional treatment with immune-supporting supplements, particularly those known to modulate and stimulate the immune system. These supplements may also provide support in cancer prevention and treatment, alongside conventional medicine.

Medicinal mushrooms have been used therapeutically for millennia and of late have been the subject of great research. Their application seems to be endless and have been used by doctors, naturopaths and health practitioners worldwide. Reishi in particular has been shown to be the therapeutic mushroom of reference in some viral infections (e.g., herpes). Due to their high content in beta-glucans, medicinal mushrooms are proven to help against many viral infections, including:

parainfluenza and rhinoviruses (common cold)

influenza (flu)

herpes simplex (HSV-1 and HSV-2)

herpes zoster or shingles (Varicella zoster virus)

mononucleosis (Epstein-Barr virus)

cytomegalovirus

hepatitis viruses, and many more.

Gut reconditioning liquid supplements that can help restore a healthy gut microbiome, influencing every mucosal barrier in the body, including the vaginal canal, where infections are very common (e.g., thrush, candida overgrowth). By their ability to modulate the gut milieu, they can directly affect immune responses in the gut, preventing inflammatory responses to spin out of control and exacerbate gut hyperpermeability, and further immune activation in other parts of the body.

Micronised zeolite appear to have a greater affinity with toxicants and allow for their elimination out of the body. Other chelating agents like chlorella and coriander, can help remove toxins and heavy metals in the gut as well, preventing further immune activation and free radical damage. An excessive production of reactive oxygen species (free radicals) is known to cause damage to the DNA, proteins, and lipids. A powerful antioxidant complex may also be considered to minimise free radical damage and assist naturally-produced enzymatic antioxidants like glutathione and superoxide dismutase.

References:

1. World Health Organisation. https://www.who.int/

2. Ferlay, J. et al. (2018). Global cancer observatory: Cancer today. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today

3. Stelzle, D. et al. (2020). Estimates of the global burden of cervical cancer associated with HIV. Lancet Glob Health. (20):30459. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(20)30459-9/fulltext

4. Lei, J. et al. (2020) HPV Vaccination and the Risk of Invasive Cervical Cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 383(14), pp. 1340-1348. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1917338.

5. World Health Organization. Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240014107

6. Alaska department of Health and Social Service. http://dhss.alaska.gov/Pages/default.aspx

7. Crosbie, EJ. et al (2013). Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet. 382(9895), pp. 889–899. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60022-7

8. Manini I, Montomoli E. (2018). Epidemiology and prevention of Human Papillomavirus. Ann Ig. 30(Suppl. 1), pp. 28-32. doi:10.7416/ai.2018.2231

9. Smith JS. et al. (2007). Human papillomavirus type distribution in invasive cervical cancer and high-grade cervical lesions: a meta-analysis update. Int J Cancer. 121(3), pp. 621–632. doi:10.1002/ijc.22527

10. Stanley M. Pathology and epidemiology of HPV infection in females. Gynecologic Oncology. 117(Suppl. 2), S5-10.

11. Manini, I. Montomoli, E. (2018). Epidemiology and prevention of Human Papillomavirus. Annali di igiene : medicina preventiva e di comunita, 30(4 Supple 1), 28–32. https://doi.org/10.7416/ai.2018.2231

12. Crosbie, EJ. et al. (2013). Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet (London, England). 382(9895), pp. 889–899. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60022-7

13. Doorbar, J. et al. (2012). The biology and life-cycle of human papillomaviruses. Vaccine. 30(Suppl 5), F55–F70. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.06.083

14. Mattoscio, D. Medda, A. Chiocca, S. (2018). Human Papilloma Virus and Autophagy. International journal of molecular sciences. 19(6), 1775. doi:10.3390/ijms19061775

15. Gulam, W. Ahsan, H. (2006). Reactive oxygen species: Role in the development of cancer and various chronic conditions. Journal of Carcinogenesis. 5, pp. 1–8. doi: 10.1186/1477-3163-5-1

15. Kraljević Pavelić, S. et al. (2018). Critical Review on Zeolite Clinoptilolite Safety and Medical Applications in vivo. Front. Pharmacology. 9:1350. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.01350