8 Ways to Avoid Burnout (at School, University or Work)

Research suggests that burnout syndrome is an indication of employee well-being and can serve as a clear measure of the connection between the individual and the workplace. But, burnout is not only a workplace problem. It is a growing concern for people working from home. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, more and more people are now working from home without properly managing their time, fixed set working hours or breaks, or meal times. Woking from home makes it very difficult for most to disconnect from work completely, and many more take work to the bedroom, disturbing their daily schedule and bedtime routine.

Students and even young children today are ill-equipped to deal with the demands placed on them like homework, studies and more so as they prepare for final exams.

Burnout is associated with impairment of mental function and impacts both the physical and mental health of individuals. It also has a pronounced socioeconomic impact in terms of reduced productivity, high resignation rates, and early retirement. In schooled children and students, it can be associated with low grade, learning difficutlies and difficulties in concentration during classes.

Given that burnout is a syndrome characterised by a collection of symptoms, accurately diagnosing this state of dysfunction is a challenge for any medical staff. According to the World Health Organisation and experts, burnout syndrome typically arises from poorly managed chronic work-, or school-related stress and constant overwhelming workload, and demands outside of office hours, or classes. The primary obstacle to diagnosing burnout syndrome lies in the absence of a standardised medical definition.

Unlike depression and anxiety, which have specific diagnostic criteria, burnout syndrome lacks a universally accepted definition and can manifest with symptoms resembling those of depression and anxiety. While depression is somewhat defined by the DSM-5, burnout remains undefined in the medical community.

Although discussions about burnout syndrome predominantly revolve around the workplace, various forms of this dysfunction can also apply to other aspects of an individual's life. Research has addressed burnout in various life domains, including relationships, caregiving, education, and parenting. Regardless of the context, burnout's core elements remain the same, including exhaustion, alienation, and reduced performance, all of which are fuelled by chronic stress.

Furthermore, a crucial characteristic of burnout syndrome involves the dysregulation of the limbic system, which can impact neural activity and function. The limbic system is a set of brain structures, which support a variety of functions including emotion (e.g., fear, pleasure, anger), behaviour (i.e., hunger, sex, dominance, care of offspring), long-term memory, and olfaction.

Dysregulation of the limbic system contributes to poor mental performance and non-melancholic depression. This type of depression is associated with dysregulated glucose metabolism, increasing the risk of metabolic syndrome or Type 2 Diabetes later in life.

“The primary obstacle to diagnosing burnout syndrome lies in the absence of a standardised medical definition.”

Risk Factors:

Certain professions are particularly susceptible to burnout, including nurses, paramedics, teachers, healthcare practitioners, lawyers, doctors, and police officers. These professionals often display dedication, workaholic tendencies, a willingness to work overtime, and a pronounced "helper syndrome." Additionally, personality traits, such as negative self-perception, contribute to burnout.

The cultural emphasis on overcommitment also heightens the risk of developing burnout syndrome.

A cross-sectional study in 2020 revealed that women face a higher risk of developing burnout syndrome, regardless of their socioeconomic status, living arrangements, or educational level.

A poor working environment and other factors, like shift work and variable hours, are believed to drive this syndrome. The convergence of workplace issues, such as unrealistic targets, shifting success criteria, high levels of responsibility, and a lack of influence opportunities, further increases the likelihood of burnout syndrome.

Common Causes of Work-related Burnout

Work-related burnout can result from a combination of various factors, and it's often a complex interplay of these elements. Here are some of the main causes of work-related burnout:

Excessive Workload: Having an overwhelming amount of work, tight deadlines, or unrealistic expectations can lead to burnout. When you constantly feel like you're drowning in tasks, it's difficult to maintain a healthy work-life balance.

Lack of Control: Feeling powerless or not having control over your work can contribute to burnout. Micromanagement, rigid work environments, and limited autonomy can be especially draining.

Lack of Recognition and Reward: When employees feel that their efforts go unnoticed or unrewarded, they may become demotivated and eventually burn out.

Unfair Treatment: Discrimination, favoritism, and workplace injustice can create a toxic environment that contributes to burnout.

Poor Work-Life Balance: An inability to separate work from personal life can lead to chronic stress. This can happen when work-related demands spill into personal time, or when employees feel they must constantly be "on call."

Lack of Social Support: Feeling isolated or disconnected from colleagues and supervisors can be emotionally draining. Social support is crucial for coping with workplace stressors.

Unclear Expectations: When employees are unsure about their roles, responsibilities, or what's expected of them, it can lead to confusion, anxiety, and ultimately burnout.

Job Insecurity: Fear of job loss or continuous job instability can cause persistent stress and anxiety, leading to burnout over time.

Limited Opportunities for Growth: A lack of opportunities for skill development or career advancement can lead to a sense of stagnation, which can contribute to burnout.

Workplace Culture: A toxic workplace culture characterized by bullying, harassment, or a lack of respect can be a major factor in burnout.

Physically Demanding Work: Jobs that require constant physical exertion, exposure to hazards, or long hours can lead to physical and mental fatigue, increasing the risk of burnout.

Emotional Labor: Jobs that require the constant management of emotions, such as customer service or caregiving roles, can be emotionally draining and increase the risk of burnout.

High-Stress Environments: Some professions inherently involve high levels of stress, such as emergency services, healthcare, or law enforcement, which can contribute to burnout if not managed effectively.

Technology Overload: Constant connectivity through smartphones and emails can make it difficult to disconnect from work, leading to burnout.

Common Causes of Burnout in School Children and Students

Burnout in students and school children can be caused by a combination of factors, many of which are related to academic, social, and personal pressures. Here are some of the main causes of burnout in students and school children:

Academic Pressure: This can include excessive homework, assignments, and exams, high expectations from parents, teachers, or self-imposed pressure to excel academically, and competitive academic environments.

Time Management Challenges: Balancing schoolwork with extracurricular activities and part-time jobs, or a lack of time for relaxation and hobbies.

Lack of Sleep: Particularly, irregular sleep patterns due to late-night studying or excessive use of electronic devices, and insufficient sleep leading to fatigue and difficulty concentrating.

Social Pressure: Peer pressure to conform or engage in risky behaviours. But also, social isolation or difficulties in forming meaningful relationships.

Bullying and Cyberbullying: Harassment and bullying from peers can lead to emotional distress and burnout.

Perfectionism: Striving for unrealistic standards of perfection in academics, appearance, or extracurricular activities.

Parental Expectations: High expectations and pressure from parents to perform academically or in extracurricular activities.

Extracurricular Overload: Being involved in too many extracurricular activities, leaving little time for relaxation and downtime.

Financial Stress: Concerns about tuition fees, college expenses, or financial instability at home.

Uncertainty About the Future: Concerns about career choices, college admissions, and the pressure to make important life decisions.

Technology and Social Media: Overuse of electronic devices and social media, leading to decreased focus and increased anxiety.

Health Issues: Physical health problems or chronic illnesses that can impact school attendance and performance.

Lack of Support: Inadequate support from parents, teachers, or counsellors.

Excessive Extracurricular Demands: Pressure to excel in sports, arts, or other activities outside of school.

Cultural and Societal Expectations: Cultural or societal pressures to meet certain academic or behavioural standards.

Stress & Burnout Syndrome:

What's the Connection? Different individuals exposed to the same level of stress can exhibit diverse responses. Collecting objective data on stress can pose a challenge for many researchers, as stressors in life vary widely, and individual responses are influenced by factors such as perceptions of manageability.

It has been proposed that an individual's perception of life determines whether stress is manageable or unmanageable. This perception of stress is influenced by factors like the extent of change, confidence in problem-solving, and life's unpredictability. Personality also plays a pivotal role in how individuals react to their environment, with high neuroticism being a core characteristic and predictor of burnout.

During periods of stress, a cascade of physiological reactions occurs in the body, known as HPA axis activation, or the stress response. Initially, this leads to excessive activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), affecting neurotransmitter and hormone production.

Prolonged stress sustains this stress response, triggering inflammatory changes in the brain and altering mood. Additionally, stressful situations can reshape neural architecture, potentially reducing neurone density in areas like the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, which can hamper an individual's ability to cope with additional stressors.

In March 2020, UK employees reported an increased perception of stress compared to the previous year, with over 40% of the workforce feeling more susceptible to extreme stress due to a poor work-life balance. These alarming statistics underscore the long-term consequences of stress, extending beyond burnout. Research has demonstrated a strong correlation between chronic stress, burnout syndrome, and various health issues such as inflammatory, autoimmune, metabolic, and cardiovascular diseases.

In the UK, there is a lack of available data on "Burnout Syndrome," with a predominant focus on workplace stress. Most research promotes policies and procedures for stress prevention rather than the adverse effects of stress.

The Stress Response: The role of GABA and Cortisol

Co-pilots of the Stress Response: GABA & Cortisol Research indicates that changes in hormonal neurotransmitters can occur based on the type of stress. Emotional stress, for example, increases levels of norepinephrine, cortisol, and free fatty acids in the acute state, while chronic stress leads to reduced cortisol levels and a state of depletion over time.

Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA):

GABA, identified as a vital inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (CNS), is synthesised from the amino acid glutamine (and/or glutamate), along with essential cofactor nutrients such as vitamin B6, zinc, and iron. The equilibrium between glutamate and GABA levels plays a crucial role in maintaining optimal cortical activity, overseeing sensations, perceptions, memory, association, thought processes, and voluntary physical actions. Several studies have examined the dysregulation of GABA production, linking it to burnout syndrome.

Maintaining appropriate GABA levels is imperative for modulating mental and physical stress. Stress has been demonstrated to reduce both GABA production and neurotransmission. Prolonged, acute, or chronic stress disrupts the cycling between glutamate and GABA, resulting in heightened neuronal excitability, which subsequently heightens an individual's vulnerability to stress, anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances.

Extended periods of stress can elevate glutamate and noradrenaline levels within the body, promoting increased neuronal activity in the central nervous system, particularly relevant to burnout syndrome due to excessive glutamate release and prolonged activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) and sympathetic nervous systems (SNS). This cascade of events fosters inflammation within the CNS and contributes to alterations in neurotransmitter production.

Reduced levels of GABA and serotonin have been correlated with burnout syndrome. Additionally, one of serotonin's myriad roles is stabilising moods when present at adequate levels.

Cortisol:

Research has demonstrated the actions of cortisol on the body and many processed. And, much is discussed in Energise. Cortisol serves as a regulator for the stress response, inflammatory reactions, and blood sugar regulation. Indeed, one of the main role of action of cortisol is to keep levels of blood sugar, lipids and blood pressure elevated. So more energy and oxygen is available for muscle tissue to run away from danger and the mind to be more focussed and driven (to find the quickest escape route and avoid obstacle).

Cortisol levels in the bloodstream exhibit diurnal variation, with peak levels occurring in the early morning and reaching their nadir around midnight, typically 3 to 5 hours after the onset of sleep. The release of cortisol is influenced by the light and dark cycles of the environment, a process mediated through communication from the retina to the paired suprachiasmatic nuclei in the hypothalamus. Consequently, the importance of regulating exposure to sunlight and blue light cannot be ignored in hypersensitive people and those experiencing heightened stress and anxiety.

Blood sugar regulation plays a crucial role in burnout. Cortisol negate the action of insulin, which diminishes the movement of glucose through the cell membrane (leading to insulin resistance in the long term|). Additionally, the presence of cortisol in the bloodstream leads to increased hepatic gluconeogenesis. These factors collectively contribute to an elevation in blood glucose levels.

When there is an ample amount of cortisol in the bloodstream, the hypothalamus and pituitary gland release reduced amounts of cortisol-releasing hormone (CH) and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). This mechanism ensures that the release of cortisol from the adrenal glands is finely tuned to meet the body's daily requirements.

Excessive cortisol resulting from prolonged activation of the HPA axis binds to receptors in the hippocampus, impacting memory, learning abilities, and emotional regulation, intensifying the stress response due to a greater sensitivity to stressors. A stone quickly becomes a mountain!

Severe burnout is characterised by a reduced or less pronounced cortisol awakening response (CAR), elevated dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) levels, and a decreased cortisol-to-DHEA ratio. This aligns with the presentation of dysfunction in the HPA axis.

Furthermore, it was observed that antidepressants can lower cortisol levels. Studies recommend avoiding the use of antidepressants for managing burnout syndrome (Kakiashvili et al., 2013). Additionally, this research advocates for the use of salivary cortisol testing to evaluate an individual's state of burnout syndrome.

Therapeutic Approach

As already explained, burnout is an intricate condition that appears to impact both the nervous and endocrine systems. Recognising the activation of inflammatory and immune components brings the necessity of incorporating a varied spectrum of nutrients tailored to your needs. Factors such as disrupted sleep, a deficiency in nutrient-rich foods, and compromised digestive health should also be taken into account (think Omeprazole and statins). The cumulative impact of these issues can result in a depleted state.

Consider the utilisation of adaptogens to bolster your response to stress. A fundamental characteristic of adaptogens is their ability to promote internal balance within the body.

It's important to note that adaptogens do not obstruct the stress response but rather mitigate the erratic fluctuations in cortisol levels. They have the potential to enhance vitality, stability, performance, and mood stabilisation.

There is substantial evidence supporting the use of Ashwagandha, Siberian ginseng, Panax ginseng, and Rhodiola (Rhodiola rosacea) for individuals experiencing burnout, owing to the adaptogenic properties exhibited by these herbal remedies (Panossian et al., 2012). Lemon balm is also featured in the literature for its inhibitory action on the key enzymes that are involved in the breakdown of serotonin and GABA, resulting in an increase in the availability and mood regulating effects of these mood-regulating neurotransmitters (the same compounds are also found in rosemary, think aromatherapy). L-theanine, found in green tea, has been the subject of extensive research. It is shown to be supportive to the nervous system, to improve sleep quality, lower blood pressure, regulate stress levels and promote relaxation. Studies have also shown that L-theanine improves sleep quality and has a positive effect on depression and anxiety disorders.

Omega-3 fatty acids (DHA and EPA) also have a large role to play in cognitive function, increased resilience and mood. However, not technically essential (they can be formed in the body via the conversion of alpha-linolenic acid, ALA), the conversion process can be reduced by stress and other conditions, leading to inadequate levels in certain circumstances. Elevated dietary saturated fats, cholesterol, trans-fatty acids, protein deficiency, a glucose-rich diet, alcohol, adrenaline, glucocorticoids, age, diabetes, and deficiencies of pyridoxine, zinc and magnesium can inhibit the enzymes required for the (endogenous) formation of EPA and DHA. (Braun & Cohen, 2014; Liao et al., 2019)

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids have long been considered essential for brain development and function. DHA and to a lesser degree EPA, are primarily found in nerve membranes and influence fluidity, cell signalling, and inflammatory pathways.

A recent intervention study using a combination of EPA (1200mg/ day) and DHA (800 mg/ day) over a 52 weeks with over 50 junior health professionals demonstrated a reduction in mood disorders, including burnout syndrome. (Watanabe et al., 2018)

Furthermore, omega 3 fats play a vital role in the regulation of blood sugar and inflammation. Dysfunction of both are additional features of burnout syndrome.

Zinc is vital for the synthesis of serotonin and other brain chemicals. Iron si also essential for neurotransmitter biosynthesis and oxygenation and function of the brain. Gingko is also to be considered for brain oxygenation (increases blood flow t the brain) and brain function as it displays antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties.

Vitamin D deficiency has been linked to mood disorders. CoQ10 may also play a role in increasing energy as it plays on mitochondria energy production and is also protective (antioxidant effects in the mitochondrial DNA and membranes).

B vitamins as always are key players in many pathways and are required for a healthy nervous system function, neurotransmitter production and myelin sheath production. They are also important to regulate sleep. Vitamin C and vitamin E are also important. The greatest concentration of vitamin C in the human body are the nerve endings, second after the adrenals. Vitamin E helps maintain the structure of the neurological system and protect phospholipids (found in great numbers in the nerve cell membranes) from peroxidation.

Magnesium is also important. It binds to glutamate receptors, preventing neural excitation. It is also involved in nerve signalling at the junction between nerve cells (at the synaptic cleft).

Diet and Lifestyle considerations

It is essential to take proactive steps to manage stress and maintain a healthy work-life balance. Here are some of the most effective strategies to prevent burnout:

Set Boundaries:

Establish clear boundaries between work and personal life. Avoid checking work emails or taking work calls during your off-hours.

Communicate your boundaries to your colleagues and superiors so they understand your availability. The way I personally see it is very simple. If I get paid to work 9-5, at 10:00 PM I will not check my emails to respond to a urgent query or work-related thing to do — unless, I pre-agreed to it.

Time Management:

Prioritise tasks and create a schedule to manage your workload effectively.

Use time management techniques such as the Pomodoro Technique to maintain focus and avoid burnout.

Take Regular Breaks:

Incorporate short breaks into your workday to recharge. Even a few minutes away from your desk can make a significant difference.

Use longer breaks for activities that relax you, like a short walk, deep breathing exercises, or meditation.

Delegate and Share the Workload:

Don't hesitate to delegate tasks when possible. Sharing responsibilities can reduce your workload and prevent burnout.

Collaborate with colleagues to accomplish projects more efficiently.

Self-Care:

Prioritize self-care activities, including exercise, a balanced diet, adequate sleep, and relaxation techniques.

Engage in hobbies and activities that bring you joy and help you unwind.

Seek Support and Talk About Your Feelings:

Don't hesitate to discuss your feelings of stress or burnout with friends, family, or a therapist. Sometimes, talking about your experiences can be very therapeutic.

Set Realistic Goals and Expectations:

Avoid setting unrealistic goals or expectations for yourself. Be aware of your limitations and accept that you cannot do everything.

Break down larger tasks into smaller, manageable steps.

Learn to Say No:

Politely decline additional work or commitments when your plate is already full. Saying no is a crucial skill in preventing burnout.

Mindfulness and Stress Reduction:

Practice mindfulness meditation and relaxation techniques to reduce stress levels and stay in the present moment.

Deep breathing exercises and progressive muscle relaxation can help calm your mind.

Regular Vacations and Time Off:

Take your vacation days and use them to disconnect from work completely. Avoid the temptation to check work-related messages while on vacation.

Professional Development:

Invest in your professional development to build skills that can make your work more manageable and enjoyable.

Evaluate Your Work Environment:

If your workplace culture contributes to burnout, consider discussing changes with management or exploring new job opportunities in a healthier work environment.

Recognise the Signs:

Be aware of the signs of burnout, such as chronic fatigue, irritability, reduced productivity, and physical symptoms. Early recognition can help you take action.

The Pomodoro Technique is a time management method developed by Francesco Cirillo in the late 1980s. It is designed to improve productivity and focus by breaking work into intervals, traditionally 25 minutes in length, separated by short breaks. The technique is named after the Italian word for "tomato" because Cirillo initially used a tomato-shaped kitchen timer as a university student to time these intervals.

Here's how the Pomodoro Technique works:

Choose a Task: Select a task you want to work on.

Set the Timer: Set a timer for 25 minutes (one Pomodoro).

Work on the Task: Work on the chosen task with full concentration until the timer rings. Avoid all distractions and interruptions during this time.

Take a Short Break: When the timer goes off, take a 5-minute break. Use this time to stretch, relax, or do something unrelated to work.

Repeat: After the break, return to your task and continue for another Pomodoro (25 minutes). Repeat this process.

Longer Break: After completing four Pomodoros, take a longer break of 15-30 minutes. This extended break helps recharge your energy.

The Pomodoro Technique may be effective because:

It provides a structured and manageable way to tackle tasks, making them feel less overwhelming.

The frequent breaks help prevent burnout and maintain focus.

It encourages you to work with a sense of urgency during the Pomodoro periods.

It helps you become more aware of how you spend your time.

You can use a physical timer, a smartphone app, or a computer-based timer to implement the Pomodoro Technique. Many apps and online tools are specifically designed to support this method, offering features like task tracking and statistics to help you optimize your work patterns.

The idea of incorporating short breaks for improved productivity is not unique to the Pomodoro Technique; it has been studied and recognised by researchers and even Henry Ford. He is a part of various productivity and time management theories.

Henry Ford, the founder of Ford Motor Company, implemented the concept of "standardised work" in his factories, which included scheduled short breaks for workers. Ford believed that giving workers short breaks allowed them to rest, recharge, and ultimately become more productive when they returned to their tasks. This approach aimed to prevent burnout and fatigue and optimise worker efficiency on the assembly line.

The key takeaway from such studies and practices, including those of Henry Ford and the Pomodoro Technique, is that regular breaks can boost productivity by improving focus, reducing fatigue, and enhancing overall well-being.

When it comes to lifestyle, setting new habits to increase your resilience and cope better under pressure (in any aspects of life) is extremely important; however, recognising the bad habits you may have developed or the lack of healthy coping mechanisms may be more important if you want change and cope better with change.

This require self-analysis and personal work. Recognising the impact of your thoughts and inner dialogue on your behaviour is key. You cannot grow and take care of yourself if the language you use in your head is harsh, critical and demeaning, virtually creating barrages that may become mountain to cross. Do not give in to your inner saboteur, no matter what you were forced to believe growing up, no matter your shortcomings, because we all have strengths and, believe it or not, weaknesses. So do not let failure define you. You are not your failure. They are a form of experience to help you be more focused, knowing what can go wrong. So fail, and fail again, until you succeed, and be your greatest supporter.

“Do not let failure define you. You are not your failure. They are a form of experience to help you be more focused, knowing what can go wrong. So fail, and fail again, until you succeed, and be your greatest supporter. ”

Mind and Body Therapies

If you understand where you are coming and aware of your learned responses to stress, then you can start working towards changing your behaviour in a stressful situation. Consider CBT or counselling, but also hypnosis and mindfulness. The later, once mastered, can truly help you take control of your thoughts and emotions, and thus your behaviour, by taking control of the narrative and being present, focussing on yourself.

A Creative Mind

Inspiration… What is it? What is its driver? Most great works of art, let it be music or painting, have been created out of an urge to express inner distress, and many people find this kind of therapy helps them deal with stressors in their lives.

Do not pretend you do not have an ounce of creativity inside of you… Because, you know it is not true. It can be writing, moving your body a certain way and dancing, it can be drawing, painting, graffiti or street art, or doodling, knitting, DIY or gardening.

Aromatherapy

Some smells make us run a mile while others are soothing and bring great memories of the past. Aromatherapy is so powerful that it cannot be overlooked. Studies have shown that rosemary oil, when diffused, contributes to increased mental focus and clarity of mind. Lavender essential oil has been extensively studied for its capacity to increase serotonin activity leading to antidepressant, anxiolytic and cognitive-enhancing effects, as well as being a great sleep aid. But, it is important to note that a little suffice, as overexposure can also be stimulant.

Do not Underestimate the Power of sleep

If you do not sleep enough, one night or every night, the repercussions on the body and the mind are immense and may impede even the simple tasks the body must execute, including movement, cognition, methylation (cellular and liver detoxification and the elimination of toxins), . Plus, you may experience a lesser threshold to pain (also, exacerbate by glutamate).

You must realign your circadian rhythm and for that you need to create a sleep hygiene, which includes exposure to sunlight in the early hours of the morning and reduce your exposure to blue light screen in the evening, a time when you should prepare you body and mind for sleep.

Lutein and zeaxanthin have been shown to reduce the time it takes to fall asleep and help to maintain a restful night sleep. Magnesium (again and again, the magic nutrients that we are desperately missing in our diet) bysglycinate is also shown to be the most effective form of magnesium for sleep. As always, regular intake for, at least, six months shows the best results. (Juturu, V. 2018; Stringham, JM. et al. 2017)

To exercise or not exercise, that is the question…

Or, is it?

Exercise, ABSOLUTELY!!!

BUT…

You need to move for things to move. Stagnation is associated with stagnation of thoughts, rumination and anxiety disorders. You cannot aspire to become more resilient if you all you do in your spare time is seat in front of the TV and snack on ultra-sweet and ultra-salty junk foods.

There is a sign of caution!

You should not exercise too close to bedtime because your body needs time to regulate temperature and you may find it more difficult to fall asleep.

Also, lower concentrations of cortisol linked to burnout syndrome (or near burnout) may require you to take it slow and gentle. Engage in low intensity activity to reduce the stimulant effect of cortisol and support your parasympathetic nervous system response, like stretching, walking, yoga (either restorative or gentle), and tai chi. Avoid strenuous activity.

Dietary Considerations

It is essential to consume a balanced diet, packed with nutritious wholesome foods, such as fruits and vegetables, pulses and legumes, nuts and seeds, good fats and lean protein. Proteins are so important during heightened stress periods, as in any time, to support many bodily functions. But also because, when under stress, you may crave (and snack more often) carbohydrate-rich foods above all else, and over-consume sugary stuff at the expense of a healthier meals. Stress can also induce protein breakdown from lean muscle tissue to sustain the fuel needed for the stress response. To prevent muscle loss, you must ensure an appropriate protein intake.

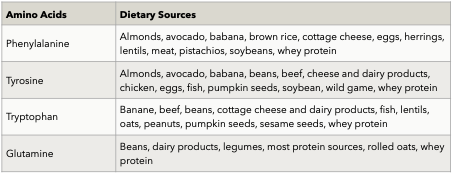

Additionally, there are key amino acids that are required for neurotransmitter production, including phenylalanine and tyrosine for dopamine and epinephrine production, tryptophan for serotonin production, and glutamine for GABA production.

If you are feeling stressed, overwhelmed, anxious or depressed, you must give particular attention to meal time, and eat at regular intervals. Remember that the stress response is very taxing on the body and you need to supply that energy. You must become a mindful eater and eat in a totally relaxed atmosphere. You must become selfish during meal times and you mustn’t be disturbed under no circumstance. If you eat at your desk, warn your colleagues and manager that you are off-limits.

DO NOT SKIP MEALS!!!

you may feel unable to eat in the morning, but in that case having something to eat, however, small is essential. It is cortisol that is telling your brain that it is in control, and YOU DO NOT WANT THAT. You must tell cortisol that YOU ARE IN CONTROL!

DO NOT EAT ON THE RUN!

If you do not give a chance to your digestive system, you will not digest the food you eat and, worse, you may feel either sleepy or bothered by gut problems. So chew your food thoroughly and mark a pause before putting that fork to your mouth. Take 2 minutes to pray, mediate, breathe or use a relaxation technique such as tapping, visualisation or gratefulness.

AVOID EMPTY CALORIES AND WATCH YOUR CAFFEINE CONSUMPTION.

Drink plenty of water to keep you hydrated and prevent constipation, a consequence of the stress response.

Restrict alcohol intake. Be aware of side-effects of pharmaceuticals and drugs.

Burnout is a very severe condition and can lead to hospitalisation in extreme cases, with many months to recover. So, dealing with stress is the best starting point. Learn to develop healthy coping mechanisms.

Analyse your diet and lifestyle and understand that you need time to change, to adapt to change. It will require work and patience, but the majority of people who have experienced burnout, myself included, will tell you that it was a life lesson learned and that it reminds us to be more focused on ourselves and needs, and to reevaluate our priorities and focus on what is really important in life, and that is family, friends and a good job where we are allowed to grow and thrive.

References

Aggarwal, R. et al. (2017). Resident wellness: An intervention to decrease burnout and increase resiliency and happiness. MedEdPORTAL: Journal of Teaching and Learning Resources. 13, 10651. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10651

Bamett, MD. Flores, J. (2016). Narcissus, exhausted: Self-compassion mediates the relationship between narcissism and school burnout. Personality and Individual Differences. 97, -pp. 102-108. doi:10.1016/.paid.2016.03.026

Bauernhofer, K. et al. (2018). Subtypes in clinical burnout patients enrolled in an employee rehabilitation program: Differences in burnout profiles, depression, and recovery/resources-stress balance. BMC Psychiatry. 18, 10. doi:10.1186/s12888-018-1589-y

Bone, K. Mills, S. (2012). Principles and Practice of Phytotherapy: Modern Herbal Medicine (Elsevier. Ed.)

Braun, L. Cohen, M. (2014). Herbs and Natural Supplements, Volume 2: An Evidence-Based Guide (Vol. 1-2).

Cao, X. Naruse, T. (2019). Effect of time pressure on the burnout of home-visiting nurses: The moderating role of relational coordination with nursing managers. Japan Journal of Nursing Science. 16(2), pp. 221-231. doi:10.1111/ins.12233

Cases, J. et al. (2010). Pilot trial of Melissa officinalis L. leaf extract in the treatment of volunteers suffering from mild-to-moderate anxiety disorders and sleep disturbances. Mediterranean Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism. 4(3), pp. 211-218. doi:10.1007/s12349-010-0045-4

Chellappa, SL. et al. (2017). Sex differences in light sensitivity impact on brightness perception, vigilant attention and sleep in humans. Scientific Reports. 7(1), 14215. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-13973-1

Chioca, LR. et al. (2013). Anxiolytic-like effect of lavender essential oil inhalation in mice: Participation of serotonergic but not GABA/benzodiazepine neurotransmission. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 147(2), pp. 412-418. doi:10.1016/.jep.2013.03.028

Ciobanu, AM. Damian, AC. Neagu, C. (2021). Association between burnout and immunological and endocrine alterations. Romanian Journal of Morphology and Embryology. 62, pp. 13-18. doi:10.47162/rjme.62.1.02

Cohen, E. (2013). Avoiding burnout. Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal. 9(2), 117. doi: 10.14797/mdcj-9-2-117

DiGalbo, RT. Reynolds, SS. (2022). Use of topical lavender essential oils to reduce perceptions of burnout in critical care. AACN Advanced Critical Care. 33, pp. 312-318. doi:10.4037/aacnacc2022289

Dyall, SC. Michael-Titus, AT. (2008) Neurological benefits of omega-3 fatty acids, NeuroMolecular Medicine. 10 (4), pp. 219-235. doi:10.1007/s12017-008-8036-z.

Eriksson, MD. et al. (2022). Non-melancholic depressive symptoms are associated with above average fat mass index in the Helsinki birth cohort study. Scientific Reports. 12(1), 6987. doi:10.1038/41598-022-10592-3

Fernandez-Fernandez, MR. et al. (2017). Hsp70 - A master regulator in protein degradation. FEBS Letters. 591 (17), pp. 2648-2660. doi:10.1002/1873-3468.12751.

Foster, JA. Rinaman, L. Cryan, JF. (2017). Stress & the gut-brain axis: Regulation by the microbiome. Neurobiology of Stress. 7, pp. 124-136. doi:10.1016/.ynstr.2017.03.001

García-Sierra, R. Fernández-Castro, J. Martínez-Zaragoza, F. (2016). Relationship between job demand and burnout in nurses: Does it depend on work engagement? Journal of Nursing Management. 24(6), pp. 780-788. doi:10.1111/ionm.12382

Golonka, K. et al. (2019). Occupational burnout and its overlapping effect with depression and anxiety. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health. 32, pp. 229-244. doi:10.13075/jomeh.1896.01323

Gonoodi, K. et al. (2018). Relationship of dietary and serum zine with depression score in Iranian adolescent girls. Biological Trace Element Research. 186(1), pp. 91-97. doi:10.1007/s12011-018-1301-6

Grensman, A. et al. (2018). Effect of traditional yoga, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy, on health-related quality of life: A randomized controlled trial on patients on sick leave because of burnout. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 18(1), 80. doi:10.1186/12906-018-2141-9

Hepburn, SJ. Carroll, A. McCuaig-Holcroft, L. (2021). A complementary intervention to promote wellbeing and stress management for early career teachers. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 18. doi:10.3390/jerph 18126320

Hidese, S. et al. (2019). Effects of L-theanine administration on stress-related symptoms and cognitive functions in healthy adults: A randomized controlled trial. Nutrients, 11(10), 2362. doi:10.3390/nu11102362

Hitl, M. et al. (2020) Rosmarinic acid-human pharmacokinetics and health benefits. Planta Medica. 87 (04), pp. 273-282. doi:10.1055/a-1301-8648.

Hoffman, D. (2003). Medical herbalism: The science & practice of herbal medicine (H. A. Press. Ed.).

Hunderfund, ANL. et al. (2022). Social support, social isolation, and burnout: Cross-sectional study of U.S. residents exploring associations with individual, interpersonal, program, and work-related factors. Academic Medicine. 97(8), pp. 1184-1194. doi:10.1097/acm.0000000000004709

Jang, HS. et al. (2012). L-theanine partially counteracts caffeine-induced sleep disturbances in rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 101(2), pp. 217-221. doi:10.1016/.pbb.2012.01.011

Jie, F. et al. (2018). Stress in regulation of GABA amygdala system and relevance to neuropsychiatric diseases. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 12. doi:10.3389/fnins.2018.00562

Jonsdottir, IH. Dahlman, AS. (2019). Mechanisms in endocrinology: Endocrine and immunological aspects of burnout: a narrative review. European Journal of Endocrinology. 180, R147-R158. doi:10.1530/eje-18-0741

Jouper, J. Johansson, M. (2013). Qigong and mindfulness-based mood recovery: Exercise experiences from a single case. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 17(1), pp. 69-76. doi:10.1016/j.jbmt.2012.06.004

Juturu, V. (2018). Lutein and zeaxanthin isomers effect on sleep quality: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research. 9(2). doi:10.26717/bistr.2018.09.001775

Kakiashvili, T. Leszek, J. Rutkowski, K. (2013). The medical perspective on burnout. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health. 26, pp. 401-412. doi:10.2478/s13382-013-0093-3

Kang, SW. Choi, EJ. (2022). Influence of grit on academic burnout, clinical practice burnout, and job-seeking stress among nursing students. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 50, pp. 1959-1966. doi:10.1111/ppc.13015

Kelly, RJ. Hearld, LR. (2020). Burnout and leadership style in behavioral health care: A literature review. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 47, pp. 581-600. doi:10.1007/s11414-019-09679-Z

Khosravi-Boroujeni, H. et al. (2017). Prevalence and trends of vitamin D deficiency among Iranian adults. A longitudinal study from 2001-2013. Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology. 63, pp. 284-290. doi:10.3177/jnsv.63.284

Kimura, K. et al. (2007). L-theanine reduces psychological and physiological stress responses. Biological Psychology. 74(1), pp. 39-45. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.006

Klier, C. Buratto, LG. (2020). Stress and long-term memory retrieval: a systematic review. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. 42(3), pp. 284-291. doi:10.1590/2237-6089-2019-0077

Knapp, S. (2020). HPA axis - The definitive guide. Biology Dictionary. Available from: https://biologydictionary.net/hpa-axis/ [Accessed 27 March 2023].

Kordzanganeh, Z. et al. (2021). The relationship between time management and academic burnout with the mediating role of test anxiety and self-efficacy beliefs among university Students. Journal of Medical Education. 20(1). doi:10.5812/jme.112142

Koushan, K. et al. (2013). The role of lutein in eye-related disease. Nutrients. 5(5), pp. 1823-1839. doi:10.3390/nu5051823

Kunno, J. et al. (2022). Burnout prevalence and contributing actors among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey study in an urban community in Thailand. PLoS One. 17, e0269421. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0269421

Lack, L. et al. (2007). Morning blue light can advance the melatonin rhythm in mild delayed sleep phase syndrome. Sleep and Biological Rhythms. 5(1), pp. 78-80. doi:10.1111/j.1479-8425.2006.00250.x

Leo, C. et al. (2021). Burnout among healthcare workers in the COVID-19 era: A review of the existing literature. Frontiers in Public Health. 9, 750529. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.750529

Liao, Y. et al. (2019). Efficacy of omega-3 PUFAs in depression: A meta-analysis. Translational Psychiatry. 9(1), 190. doi:10.1038/s41398-019-0515-5

Liu, Y. Zhao, J. Guo, W. (2018). Emotional roles of mono-aminergic neurotransmitters in major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders. Frontiers in Psychology. 9. doi:10.3389/psyg.2018.02201

Lopresti, AL. et al. (2019). An investigation into the stress-relieving and pharmacological actions of an ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) extract: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Medicine. 98(37), e17186. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000017186

Lu, FI. Ratnapalan, S. (2023). Burnout interventions for resident physicians: A scoping review of their content, format, and effectiveness. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 147, pp. 227-235. doi:10.5858/arpa.2021-0115-ep

Mahmoud, N. Rothenberger, D. (2019). From burnout to well-being: A focus on resilience. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery. 32(06), pp. 415-423. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1692710

McEwen, B. (2000) Allostasis and allostatic load implications for neuropsychopharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology. 22 (2), pp. 108-124. doi:10.1016/0893-133×(99)00129-3.

Medic, G. Wille, M. Hemels, ME. (2017). Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nature and Science of Sleep. 9, pp. 151-161. doi:10.2147/nss.s134864

Miraj, S. Rafieian, K. Kiani, S. (2016). Melissa officinalis L: A review study with an antioxidant prospective. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine. 22 (3), pp. 385-394. doi:10.1177/2156587216663433,

Miyake, M. et al. (2014). Randomised controlled trial of the effects of L-ornithine on stress markers and sleep quality in healthy workers. Nutrition Journal, 13(1). doi:10.1186/1475-2891-13-53

Murthy, SV. Fathima, SN. Mote, R. (2022) Hydroalcoholic extract of ashwagandha improves sleep by modulating GABA/histamine receptors and EEG slow-wave pattern in vitro - in vivo experimental models. Preventive Nutrition and Food Science. 27 (1), pp. 108-120. doi:10.3746/pnf.2022.27.1.108.

Musazzi, L., Treccani, G. Popoli, M. (2015). Functional and structural remodelling of glutamate synapses in prefrontal and frontal cortex induced by behavioral stress. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 6. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00060

Nasir, M. et al. (2020). Glutamate systems in DSM-5 anxiety disorders: Their role and a review of glutamate and GABA psychopharmacology. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 11. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.548505

Ogunyemi, D. et al. (2022). Improving wellness: Defeating Impostor syndrome in medical education using an interactive reflective workshop. PLoS One. 17, e0272496. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0272496

WHO. (2019). Burn-out an “Occupation phenomenon.” International classification of Diseases. Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases

Panossian, A. et al. (2009). Evidence-based efficacy of adaptogens in fatigue, and molecular mechanisms related to their stress protective activity. Current Clinical pharmacology. 4 (3), pp. 198-219. doi:10.2174/157 488409788375311.

Panossian, A., Wikman, G., Kaur, P. and Asea, A. (2012) Adaptogens Stimulate Nauropeptice Y and Hsp72 Expression and Release in Leurogia Cells, Frontiers in Neuroscience, 6. DOl:htips://doi.org/10.3389/nins.2012.00006.

Sharkey, KM. et al. (2011). Effects of an advanced sleep schedule and morning short wavelength light exposure on circadian phase in young adults with late sleep schedules. Sleep Medicine. 12(7), pp. 685-692. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2011.01.016

Spencer, RL. Deak, T. (2017). A user’s guide to HPA axis research. Physiology & Behavior, 178, pp. 43-65. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.11.014

Stephenson, LE. Bauer, SC. (2009). The role of isolation in predicting new principals’ burnout. International Journal of Education Policy and Leadership. 5(9). doi:10.22230/jepl.2010v5n9a275

Stringham, JM. Stringham, NT. O'Brien, KJ. (2017). Macular carotenoid supplementation improves visual performance, sleep quality, and adverse physical symptoms in those with high screen time exposure. Foods. 6(7), 47. doi:10.3390/foods6070047

Suzuki, E. et al. (2009). Relationship between assertiveness and burnout among nurse managers. Japan Journal of Nursing Science. 6(2), pp. 71-81. doi:10.1111/j.1742-7924.2009.00124.x

Alschuler, L. (2019). The role of cortisol. Available at: https://www.integrativepro.com/articles/the-role-of-cortisol

Uhlig-Reche, H. et al. (2021). Investigation of health behavior on burnout scores in women physicians who self-identify as runners: A cross-sectional survey Study. American Joumal of Lifestyle Medicine. 155982762110425. doi:10.1177/15598276211042573

Van Amsterdam, JGC. et al. (2015). Burnout is associated with reduced parasympathetic activity and reduced HPA axis responsiveness, predominantly in males. Biomed Research International. 2015, article: 431725. doi:10.1155/2015/431725

Vries, A. et al. (2022). Self-, other-, and meta-perceptions of personality: Relations with burnout symptoms and eudaimonic workplace well-being. PLoS One. 17, e0272095. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0272095

Watanabe, N. et al. (2018). Omega-3 fatty acids for a better mental state in working populations - Happy Nurse Project: A 52-week randomized controlled trial. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 102, pp. 72-80. doi.10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.03.015

Yao, Y. et al. (2018). Job-related burnout is associated with brain neurotransmitter levels in Chinese medical workers: A cross-sectional study. Journal of International Medical Research. 46(8), pp. 3226-3235. doi:10.1177/0300060518775003

Other Sources:

Chirico F. (2016). Job stress models for predicting burnout syndrome: a review. Annali dell'Istituto superiore di sanita, 52(3), pp. 443-456. doi.:10.4415/ANN_16_03_17

Cohen, MM. (2014). Tulsi - Ocimum sanctum: A herb for all reasons. Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine. 5(4), pp. 251-259. doi:10.4103/0975-9476.146554

Friganovic, A. et al. (2019). Stress and burnout syndrome and their associations with coping and job satisfaction in critical care nurses: A literature review. Psychiatria Danubina. 31(Suppl 1), pp. 21-31.

Güler, Y. et al. (2019). Burnout syndrome should not be underestimated. Revista da Associacao Medica Brasileira (1992). 65(11), pp. 1356-1360. doi:10.1590/1806-9282.65.11.1356

Ivanova Stojcheva, E. Quintela, JC. (2022). The effectiveness of rhodiola rosea L. Preparations in alleviating various aspects of life-stress symptoms and stress-induced conditions - encouraging clinical evidence. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland). 27(12), 3902. doi:10.3390/molecules27123902

Lianov, L. (2021). A powerful antidote to physician burnout: Intensive healthy lifestyle and positive psychology approaches. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 15(5), pp. 563-566. doi:10.1177/15598276211006626

Mental Health UK. (2021). Burnout. https://mentalhealth-uk.org/burnout

Merlo, G. Rippe, J. (2020). Physician burnout: A lifestyle medicine perspective. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 15(2), pp. 148-157. doi:10.1177/1559827620980420

Pentinen, MA. et al. (2021). The association between healthy diet and burnout symptoms among finnish municipal employees. Nutrients. 13(7), 2393. doi:10.3390/nu13072393

Ptácek, R. et al. (2019). Burnout syndrome and lifestyle among primary school teachers: A Czech representative study. Medical Science Monitor : International Medical Journal of Experimental & Clinical Research. 25, pp. 4974-4981. doi:10.12659/MSM.914205

Rodrigues, H. et al. (2018). Burnout syndrome among medical residents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 13(11), e0206840. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0206840

Rosales-Ricardo, Y. Ferreira, JP. (2022). Effects of physical exercise on burnout syndrome in university students. MEDIC Review. 24(1), pp. 36-39. doi:10.37757/MR2022.V24.N1.7

Todorova, V. et al. (2021), Plant adaptogens-history and future perspectives. Nutrients. 13(8), 2861. doi:10.3390/nu13082861