Endometriosis

What is it and how to heal naturally

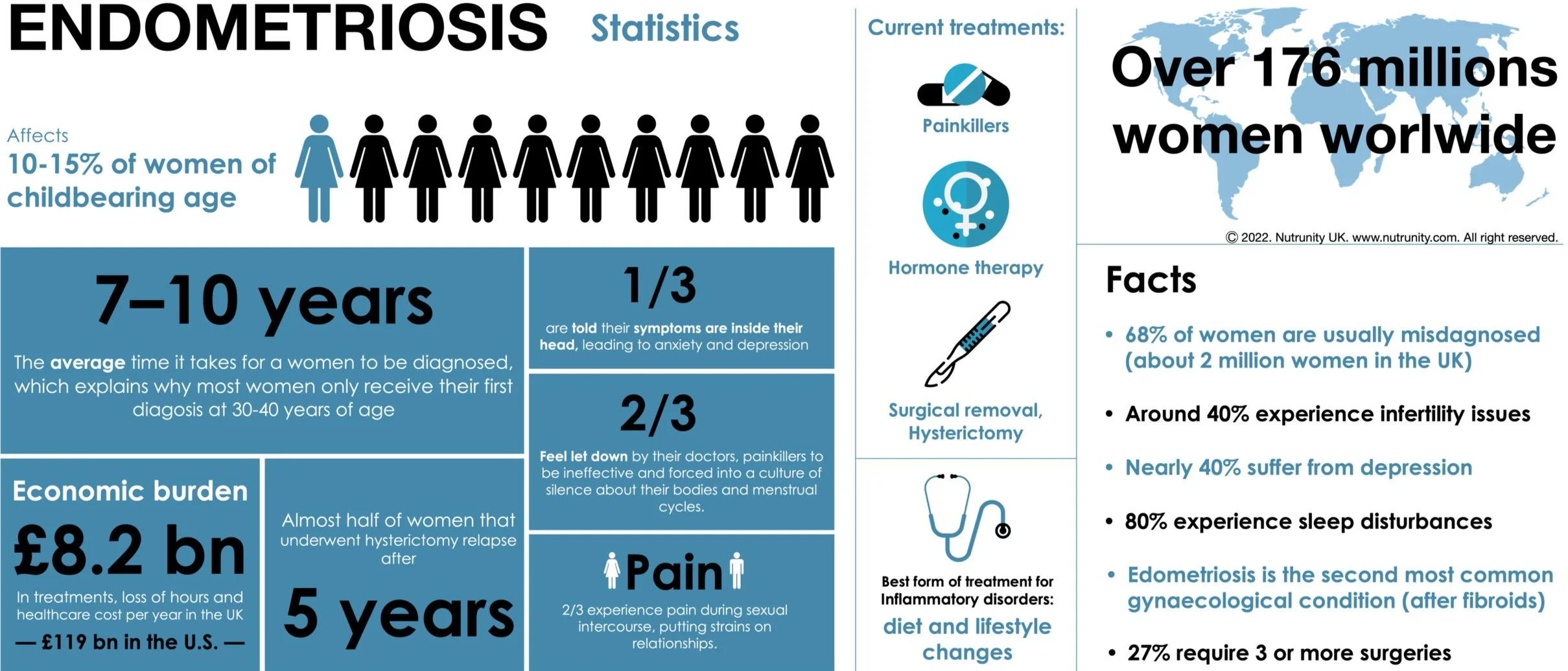

Endometriosis is a common but still poorly understood medical condition affecting 10–15% of women of reproductive age in which cells from the endometrium (the lining of the uterus) migrate outside the uterus, and which can be found on the ovaries, fallopian tubes, in the abdominal cavity and in other places throughout the pelvic area. Because these uterine cells continue to respond to monthly hormonal cycles (thickens, breaks down and bleeds with each menstrual cycle), they can wreak havoc in many ways.

In some rare cases, endometrial tissue may be found well outside the pelvic organs like the lungs, a condition called catamenial pneumothorax, causing pain and bleeding and cyclical collapse of the lung; the bowel (bowel endometriosis), which can be mistaken for IBS, or the bladder or rectum (deeply infiltrating endometriosis); the peritoneum, the thin membrane that lines the abdomen and pelvis (superficial peritoneal endometriosis); which can go from mild (stage 1 - a few small implants, or small wounds or localised lesions) to severe (stage 4 — most widespread, with many deep implants and thick adhesions. There are also large cysts on one or both ovaries). There also may be a build-up of scar tissue binding organs together.

Endometriosis may also be a problem for women that undergo cesareans as endometrial tissues can be transferred to the abdominal cavity and grow in the scar from surgery.[1]

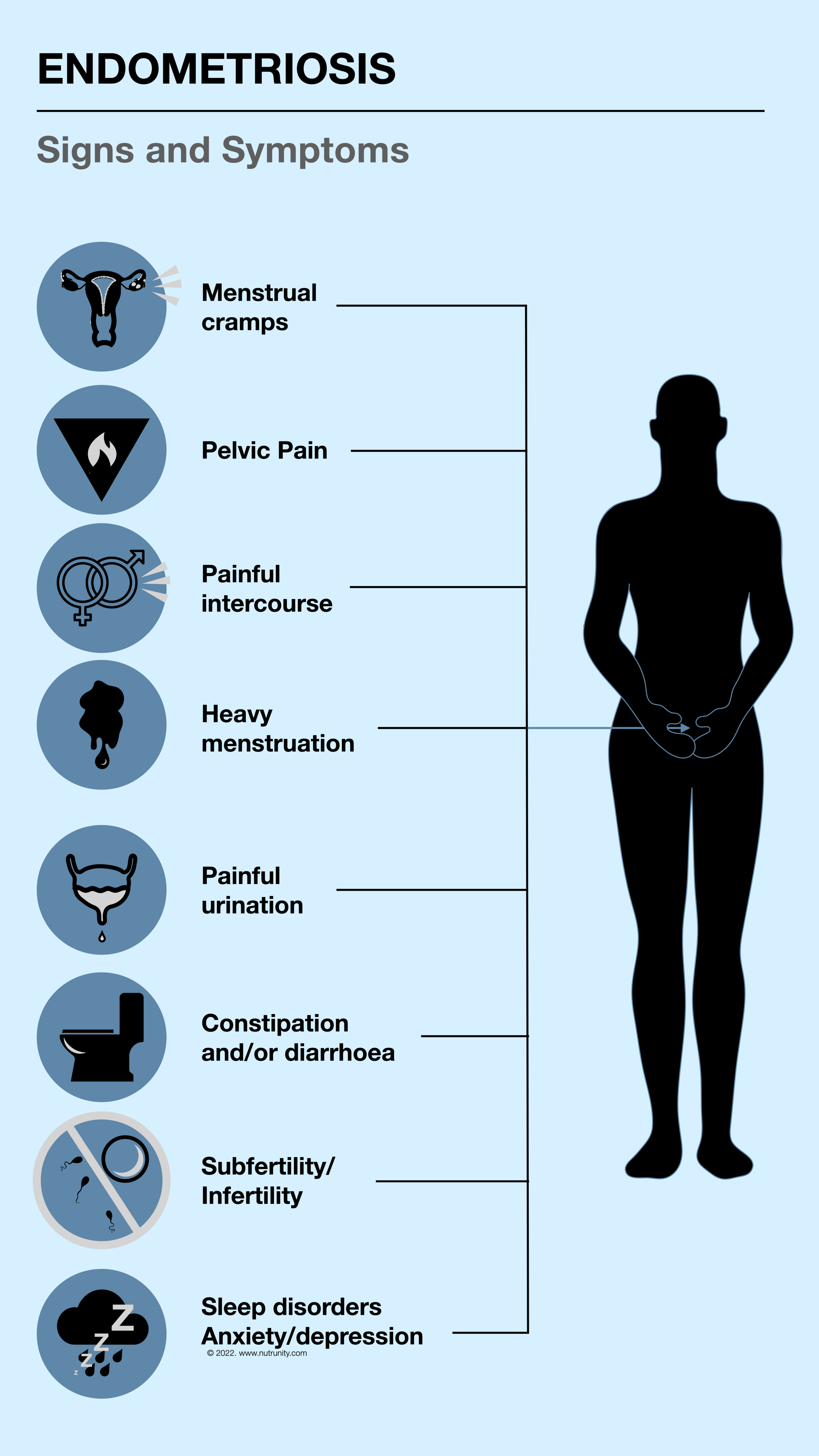

Depending on where the uterine tissue has relocated, symptoms can include painful periods (dysmenorrhea), longer bleeding periods and heavy bleeding, pain during or after intercourse (dyspareunia), persistent lower back and pelvic pain, bloating, constipation and/or diarrhoea, discomfort during bowel movements, indigestion and/or nausea during menstruation. Some women may bleed between periods.

Endometriosis is also a common cause of subfertility (difficulties conceiving) or infertility and endometrial cysts and has been shown to cause urinary issues like blood in the urine or pain with urination, and has also been linked to interstitial cystitis

“Endometriosis symptoms may include painful periods, persistent lower back and pelvic pain, bloating, constipation, infertility, and more.”

Risk factors

Risk factors include family history (risk may be increased by up to 10 times)[2,3], use of intrauterine devices, low body mass index[4], early menarche or late menopause, short menstrual cycles and longer periods (7 days or longer)[5,6], uterine growths, like fibroids or polyps, or infertility[7], conditions that may be associated with imbalanced oestrogen[8] and progesterone levels[9]. In fact, progesterone has been suggested to affect both implantation and inflammation in endometriosis.[10]

Immune dysfunction also contributes to endometriosis risk. If your immune system is suppressed or weak, it will be less likely to recognise misplaced endometrial tissue.

Late puberty and early menopause, pregnancies and breastfeeding appear to lower the risk for endometriosis.[11,12,13]

Genetic Factors

Scientists have identified a number of genetic mutations (SNPs) closely linked to endometriosis, including:

CDKN2BAS — regulates tumour suppressor genes believed to be linked to endometriosis

EMX2 — critical for the development of the central nervous system and genitourinary system

GREB1/FN1 — helps regulate oestrogen production

GSTM1 and GSTT1 — involved in the detoxification of a broad range of toxic compounds and carcinogens, including dioxin

HOXA10 — regulates differentiation of the endometrium in preparation for embryonic implantation and may be implicated in infertility

HSD17B1 — has a dual function in oestrogen activation and androgen inactivation and plays a major role in establishing the oestrogen concentration gradient between serum and peripheral tissues

MUC16 — responsible for forming protective mucus layers in the uterus

VEZT — aids in the creation of tumour suppressor genes

WNT4 — vital to the development of the female reproductive tract

While genetics play a great part, the environment (diet, lifestyle, stress management) may also have a role to play. For example, a diet high in trans fats and poor in plant-based nutrient-dense foods[14], high caffeine and alcohol consumption of alcohol and a sedentary lifestyle[15], have all been implicated in endometriosis.

Exposures to endocrine-disrupting chemicals, such as dioxin, have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of endometriosis and any factors affecting detoxification pathways.

Diagnosis

Physicians diagnose endometriosis based on findings during a pelvic exam, presenting symptoms and a thorough medical history. During the pelvic exam, your doctor manually palpates areas in your pelvis for abnormalities, such as cysts or growths on your reproductive organs or scars behind your uterus. Transvaginal ultrasound and MRI can be requested for differential diagnosis.

The gold standard for diagnosing endometriosis is a laparoscopy (keyhole surgery).

It may take up to 10 years for a woman to be diagnosed. This explains why women are typically diagnosed in their 30s and 40s. Most of the time, doctors will prescribe painkillers and tell you that period pains are normal and to your face that it’s all in your head, leaving you to deal with the problem and find solutions by yourself.

This is what Wendy K Laidlaw said in a recent interview:[16]

“I had been embroiled in the medical system since my endometriosis began at the mere age of 11 and it had finally left me dangerously ill. Since then, I had gone through six surgical procedures, all of which failed to make me better and instead bestowed upon me more symptoms and additional side effects like adhesions and cysts. I was prescribed a range of drugs and supplied with an arsenal of painkillers but it was all to no avail. Nothing they offered to me could tame the spread of my endometriosis and abate the pain. Eventually, the doctors treated me like a nuisance, some sort of hysterical female…

Some medical professionals even went as far as to the reason that their ‘medical tools’ were not working for me because I was attention-seeking and just imagining all my conditions. In short, the gynaecological professionals washed their hands of me. They couldn’t ‘fix’ me so it was best to just ignore me. That wasn’t without lastly suggesting a hysterectomy, which is a barbaric surgery that involves removing all of a woman’s reproductive organs. It is wholly unnecessary and ineffective in almost all instances. I knew this though.

My mother had suffered terribly from endometriosis as well and she had been strongly advised to get a hysterectomy. She did and sadly, all of her endometriosis symptoms came back but with added ferocity and insult of additional symptoms and conditions.”

Conventional Treatments

According to conventional medicine endometriosis is a chronic, oestrogen-dependent disorder and therefore generally occurs when endometrial tissue grows abnormally and adheres outside of the uterus. Endometriosis (EM) has a high prevalence rate in women of reproductive age and is divided into ovarian EM, peritoneal EM, and deep infiltrating EM according to the sites of implantation.

The most common site is the ovary and the most common symptom is chronic pelvic pain, notably dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia, and infertility, which all may lead to a reduction in the patient's quality of life. EM rarely undergoes malignant transformation but, with it, there is a rising risk of ovarian, breast and other cancers as well as autoimmune and atopic disorders.[17]

Research continues to examine other risk factors which may be potentially involved in the formation of EM, including genetics [18], immune factors [19], inflammatory factors [20], ectopic endometrium specificity, and environmental toxins [21]

However, symptoms are typically managed with hormonal medication to suppress the natural menstrual cycle, in addition to painkillers to manage the pain. Hormone replacement therapy involves oral contraceptives, progestogenics (progesterone creams), gestrinone, Danazol (androgen derivates), and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists.

Long-term administration with these therapies remains challenging due to the plethora of serious adverse effects involved, such as massive haemorrhage, perimenopausal stage symptoms, masculinising manifestation, and liver dysfunction. Data from the Cleveland Clinic showed that EM recurrence rates ranged between 20% and 40% within five years following conservative surgery, which means that a conventional approach doesn’t offer long-term relief and may work against the body’s healing capacities.[22]

Worse, some women may be led to believe that a hysterectomy, the most aggressive form of treatment, is the only and best procedure to reduce the symptoms, but as discussed earlier this is not the case.

Additionally, research has demonstrated time and time again that regular intake of painkillers and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can erode the lining of the digestive tract and lead to lesions (and bleeding) and may be involved in intestinal hyperpermeability (leaky gut syndrome), further fuelling inflammatory responses and hyper-reactivity of the immune system.

“A conventional approach doesn’t offer long-term relief and may work against the body’s healing capacities.”

A natural approach

In recent years, the complementary and alternative medical (CAM) treatment for endometriosis has become popular due to the few adverse reactions reported. Complementary and alternative medicine differs from mainstream medicine and is widely accepted as a kind of medical treatment, and encompasses all health systems, practices, and modalities.

Nonpharmacologic interventions, like naturopathic medicine and nutrition, can reduce pain and concomitant mood disturbance to increase the quality of life by employing mind-body interventions.[23,24]

The CAM therapies for endometriosis with proven results include herbal products, acupuncture, Chinese herbal medicine enema, and psychological (stress management) interventions.[25]

Understanding the multifaceted causes of endometriosis gives the blueprint for the treatment of both acute and long-term issues. Personalised protocols begin with stimulating the body's innate ability to heal by restoring a healthy inflammatory response, balancing hormones, and assisting the liver's ability to break down environmental toxins as well as oestrogen.

Naturopathic treatment considers the patient as a whole. For many women, endometriosis can lead to high levels of stress and anxiety, often due to the pain (and sleep disturbances), difficulty in diagnosis and no long-term solutions for an often invisible disease. NDs’ aim is to heal not only the body but also the symptoms of mind and spirit.

The naturopathic approach to endometriosis focusses on:

Reducing inflammation

Enhancing detoxification (especially of excess oestrogen)

Reducing symptoms

Balancing hormones

Stress management

Inflammation

Inflammation is a major contributor to endometriosis. The Nurses' Health Study II found that women who consumed the most trans fats (hydrogenated vegetable oils used in processed foods) were 48% more likely to be diagnosed with endometriosis. Women with a greater intake of omega-3 fatty acids were 22% less likely to be diagnosed with endometriosis. Improving the ratio of omega-6 fatty acids to omega-3 (2:1 to 3:1) also helps reduce inflammation. A typical Westernised diet has a ratio of 16:1 or more. For this reason, the SAD (standard American) diet is a pro-inflammatory type of diet and is a leading cause of disproportionate inflammatory responses in the body. Additionally, people consuming this type of diet have a tendency to not exercise or take part in feel-good physical activities.

In a study of 500 women, a significantly reduced risk of developing endometriosis was found with greater consumption of fruits and vegetables.[25] Conversely, an increased risk of endometriosis was associated with higher consumption of (conventional) red meat. A greater intake of dietary fibre is associated with a healthy balance of microorganisms in the gut flora, where they play an important role in breaking down oestrogen and also in keeping inflammation processes in check. Studies show that the inclusion of soy with its isoflavones can reduce the proliferation of endometrial cells.[26] It is important to note that research on isoflavones relies on an intake of fermented soy products from a young age and that a later intake(e.g., from adolescence onwards) shows to have no therapeutic effect.

Antioxidants are very relevant to the prevention and reversal of tissue damage observed in endometriosis. It is, therefore, important to increase your intake of antioxidants by consuming 5-10 portions of fruits and vegetables (ideally organic) daily. Vitamin C, A and E are important nutrients. Resveratrol, N-Acetyl cysteine, pine bark, green tea and melatonin have been studied for their powerful antioxidant benefits with some interesting results.

Detoxification

Unobstructed liver and bile systems and elimination channels are a prerequisite to prevent the stagnation of waste and the re-entry of toxins and detoxified hormones into the circulation (via a toxic colon).

Chronic constipation is not ‘normal’ and may indicate a diet poor in fibre, food intolerances and/or allergies, over-consumption of ultra-processed manufactured food products, gut inflammation, and poor hydration. Constipation may also increase the risk of a toxic colon, putting strain on the bacteria that we rely on to keep our intestinal tract tight and permeable and also vitamins that we could not assimilate otherwise.

Detoxification starts with reducing the toxic load. This can only be done by looking at what you put at the end of your fork, on your skin, and in the air you breathe (e.g., indoor pollution, which may include solvents, detergents, insecticides, fire retardants, phthalates and other products from the breakdown of plastics, and heavy metals).

A calorie-restricting diet may also overwhelm the liver by directing toxins from fatty tissue (where they were stored); therefore, a sudden loss of body weight can lead to cold and flu symptoms, chills, fatigue and an overall sensation of malaise.

To support liver function, a nutrient-dense, balanced diet is required as so many nutrients are involved in detoxification but some also act as co-factors in many enzymatic activities.

Liver detoxification pathways requirements

Balancing hormones

Already established as decisive factors, diet and avoiding toxic substances, particularly xenoestrogens, are here as well essential to balance hormones.

Xenoestrogens can mimic endogenous hormones, antagonise their interaction with oestrogen receptors or disrupt the synthesis, metabolism and functions of endogenous female hormones — deeply interfering with endocrine processes. Xenoestrogens are collectively called endocrine disruptors. There are many sources of xenoestrogens, that is not only vegetables and fruit (phytoestrogens), but also heavy metals (e.g., cobalt, copper, nickel, chromium, and lead), dental appliances (alkyl-phenols), plastic containers, cling film, or blood containers (e.g., PVC and phthalates), cosmetics (e.g., parabens and phthalates) and pesticides (e.g., DDT and endosulfan).[27]

According to the working definition of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), an endocrine disruptor is:

“An exogenous agent that interferes with the synthesis, release, transport, metabolism, binding, action, or elimination of natural hormones in the body responsible for the maintenance of homeostasis, reproduction, regulation of developmental processes and/or behaviour”[28]

Endocrine disruptors comprise more than 100.000 synthetic chemical compounds that belong to different classes. A subset of the endocrine disruptors, including synthetic oestrogens, natural products, commercial chemicals, industrial compounds, or by-products among which plastics, are known as environmental oestrogens or xenoestrogens — they confer oestrogenic potential (“oestrogenicity”)

The problem is our bodies cannot make the distinction between an actual oestrogen and a xenoestrogen. And so it is important to keep away from this when looking to balance hormones. The increased exposure to these endocrine disrupters in modern living explains in part the increased challenges with many hormonally driven conditions.[29]

Use natural skincare products and avoid harsh chemicals (e.g., detergents, insecticides, fabric conditioners). It is also possible to make your own (https://www.nutrunity.com/ecoliving-blog). Eliminate plastic from your life as much as possible. Never drink bottled water unless it is in a glass bottle. Never drink coffee from a takeaway cup and with the plastic lid on. Instead, carry your glass takeaway cup or stainless still flask with you.

Managing stress

Hormones can have a widespread effect on the body and any imbalance may lead to health problems. Due to their dominating effects, a higher concentration of stress hormones like cortisol can make difficult the task of balancing hormones. Stress hormones must also be included in hormone screening (e.g., DUTCH test). When stress becomes chronic and plasma cortisol remains elevated, progesterone can drop leading to unpleasant symptoms such as moodiness, increased weight around the middle, sleep problems and breast tenderness.

Supplementing with magnesium and adaptogens (e.g., herbs and medicinal mushrooms) can help balance the body’s response to stress. Meditation, yoga and other forms of meditative exercise like Qi gong, regular massages, journaling and mindfulness are techniques to incorporate in your day to help you better deal with stress and increase your resilience.

Inflammation is a huge stressor for the body. Identifying food allergies and hypersensitivities (IgG-led), and removing triggers are all essential. Gluten, in particular, has been shown to be a contributing factor to endometriosis and studies have shown a significant reduction in symptoms following a gluten-free diet. If you can’t afford a food intolerance test, you may follow an elimination and monitor symptoms as you reintroduce foods in your diet.

Endometriosis has a strong link with IBS. Following an anti-inflammatory diet has been found to be supportive of both conditions.

Supplementation

NAC (N-acetyl cysteine ). A 2013 study, which included 92 women with endometriosis showed that following a three months supplementation with NAC for three days in a week led to cancellations of laparoscopic visits due to a reduction in symptoms.[30]

Pycnogenol from pine bark. In a Swiss study, women either received pycnogenol or GnRH (gonadotropin-releasing hormone) for 48 weeks. Both groups showed a reduction in symptoms. However, once treatment stopped the benefits in the pycnogenol group lasted while the GnRH group relapsed after treatment.

Melatonin. A randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled study (2013) looked at the analgesic, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of melatonin in endometriosis with some very promising results.[31] Apart from improving sleep, 80% of patients given melatonin didn’t require analgesics. Supplementation with melatonin must be closely monitored and built up to recommended intake (10mg).

Other forms of treatment: Herbal Medicine (under practitioner surveillance)

Typically a combination of any the following given in capsules, herbal preparation or enema decoction (therapeutic effectiveness >90%)[32,33]:

Artemisinin

Chinese Angelica

EGCG from green tea (polyphenols)

Frankincense

Ginger

Honeysuckle Flower

Largeleaf Gentian Root

Myrrh

Peach seeds

Red Peony Root

Resveratrol (polyphenols)

Saffron

Sichuan lovage rhizome

Skullcap

Turmeric (curcumin)

Several of the compounds listed above are also found in many plants and so a diet rich in nutrients, particularly phytonutrients, is always a predominant factor in prevention. These compounds appear to be useful in any therapeutic approach where inflammation is a problem.

Other forms of treatment: Acupuncture

Acupuncture and Moxibustion treatment is one of the traditional Chinese practices widely used in China and some Asian countries. The aim is to restore the flow of Qi (chi) and to improve the body's immune function to relieve symptoms of endometriosis (therapeutic effectiveness ≥93%).[32]

In conclusion:

As a result of generalists failing their patients, a multitude of women are being misdiagnosed and suffering in silence, ignored and forced into a culture of silence about their body and menstrual cycles. Worse of all, they are told by their doctors that their pain is not real and that it is all in their head.

Why?

Because they do not refer their patients to the right services and requests tests that are inadequate and also because they don’t know much about women’s reproductive health, and frankly some don’t care. They don’t have the time nor the energy to go out of their way to investigate the problems. My local surgery has 15,000 patients. It is literally impossible to care efficiently for that many people. Period. A consultation of 5-9 minutes is not enough to review symptoms and LISTEN to the complaints their patients have.

In Naturopathic Medicine, Functional Medicine and Nutrition, our aim is to re-establish balance and allow for the body to heal. We offer initial consultations that may last up to 2 hours. During this time, we look at your body from every angle, the way your body and mind function and interact together, and identify and potential energetic imbalances that may lead to dysfunction. This level of attention will never be given by your doctors. They belong to the diseasecare not healthcare — they medicate you without any inclination to understand why. This also explains why a women with endometriosis sees FIVE different physicians before receiving a diagnosis.

Some factors that may contribute to endometriosis may include genetics, hormonal imbalance, environmental exposure, and immunological dysfunction. Interventions, therefore, have to include diet and lifestyle changes, as well as stress management and testing for food allergies and intolerances, genetic specificities, and hormonal balance.

A comprehensive blood test with liver and kidney function may also be recommended. Fasting blood glucose and HbA1c are also key factors to consider.

The recommendation of an anti-inflammatory diet is often part of the plan in order to reduce inflammation and help with the balance of oestrogen.

References

Andolf, E. Thorsell, M. Källén, K. (2013). Caesarean section and risk for endometriosis: A prospective cohort study of Swedish registries. 120(9), pp. 1061–1065. doi.:10.1111/1471-0528.12236

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). (2019). Endometriosis. Available at: https://www.acog.org/Patients/FAQs/Endometriosis. Last accessed Mar. 12th 2022.

Dun, EC. Taylor, RN. Wieser, F. (2010). Advances in the genetics of endometriosis. Genome Medicine. 2(10), Article 75. doi:10.1186/gm196

Farland, LV. et al. (2017). Associations among body size across the life course, adult height, and endometriosis. Human reproduction (Oxford, England), 32(8), pp. 1732–1742. doi:10.1093/humrep/dex207

ACOG. (2010, reaffirmed 2018). Practice Bulletin No. 114: Management of endometriosis. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 116(1), pp. 223–236. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e8b073

Treloar, SA. et al. (2010). Early menstrual characteristics associated with subsequent diagnosis of endometriosis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 202(6), 534.e1–534.e6. doi.:10.1016/j.ajog.2009.10.857

Burney RO, et al. (2007). Gene expression analysis of endometrium reveals progesterone resistance and candidate susceptibility genes in women with endometriosis. Endocrinology. 148, pp. 3814-3826. doi.:10.1210/en.2006-1692

Dyson, M. Bulun, S. (2012 ). Cutting SRC-1 down to size in endometriosis. Nature Medicine. 18(7), pp. 1016–1018. doi.:10.1038/nm.2855

Bulun, SE. et al. (2020). Estrogen receptor-beta, estrogen receptor-alpha, and progesterone resistance in endometriosis. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine. 28, pp. 36–43. doi.:10.1055/s-0029-1242991

Peterson, C. M. et al. (2013). Risk factors associated with endometriosis: Importance of study population for characterizing disease in the ENDO Study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 208(6), 451.e1–451.11. doi.:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.02.040

Farland, LV. et al. (2017). History of breastfeeding and risk of incident endometriosis: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 358, j3778. doi:10.1136/bmj.j3778

Ashrafi, M et al. (2016). Evaluation of Risk Factors Associated with Endometriosis in Infertile Women. International Journal of Fertility & Sterility. 10(1): pp, 11–21.

Leeners, B. et al.(2018). The effect of pregnancy on endometriosis—facts or fiction? Human Reproduction Update. 24(3), pp. 290-299. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmy004

Harris, HR. et al. (2018). Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of endometriosis. Human reproduction. 33(4), pp. 715–727. Human Reproduction (Oxford, England). 33(4), pp. 715–727. doi.:10.1093/humrep/dey014

Office on Women’s Health (OASH). (2019). Endometriosis. Available at: https://www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/endometriosis. Last accessed: Mar. 12th 2022.

Brainz Magazine. (2022). Available at https://www.brainzmagazine.com/post/heal-endometriosis-naturally-exclusive-interview-with-wendy-k-laidlaw?utm_campaign=ca34c059-bfcf-47dd-9704-730a56b2d96c&utm_source=so&utm_medium=mail&cid=f3358a01-c14e-44c6-8e1e-9c7c50b99aae

Giudice, LC. Kao, LC. (2004). Endometriosis. The Lancet. 364(9447), pp. 1789–1799. doi.:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17403-5

Evian Annual Reproduction (EVAR) Workshop Group 2010. Fauser BCJM, et al. (2011). Contemporary genetic technologies and female reproduction. Human Reproduction Update. 17(6), pp. 829–847. doi.:10.1093/humupd/dmr033

Sinai, N. et al. (2002). High rates of autoimmune and endocrine disorders, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and atopic diseases among women with endometriosis: A survey analysis. Human Reproduction. 17(10), pp. 2715–2724

Wellbery C. (1999). Diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. American Family Physician. 60(6), pp. 1753–1762

Guo, S-W. et al. (2009). Reassessing the evidence for the link between dioxin and endometriosis: From molecular biology to clinical epidemiology. Molecular Human Reproduction. 15(10), pp. 609–624

The Cleveland Clinic. (2010). Recurrent Endometriosis: Surgical Management, Endometriosis. Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/4551-endometriosis-recurrence--surgical-management. Last accessed Mar. 12th 2022.

Pujol, LA. Monti, DA. (2007). Managing cancer pain with nonpharmacologic and complementary therapies. Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 107(12 Suppl 7), ES15-21.

Kellehear A. (2003). Complementary medicine: Is it more acceptable in palliative care practice? Journal of the Australian Medical Association. 179(S6), S46-8. doi.:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05580.x

Parazzini, F. et al. (2004). Selected food intake and risk of endometriosis. Human Reproduction. 19(8), pp. 1755–1759. doi.:10.1093/humrep/deh395

Takaoka, O. et al. (2018). Daidzein-rich isoflavone aglycones inhibit cell growth and inflammation in endometriosis. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 181, pp. 125–132. doi.:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2018.04.004

Wozniak, M. Murias, MK. (2008). (Polish) Ksenoestrogeny: Substancje zakłócajace funkcjonowanie układu hormonalnego [Xenoestrogens: endocrine disrupting compounds]. Ginekol Polska. 79(11), pp. 785–90.

Kavlock, RJ. et al. (1996) Research needs for the risk assessment of health and environmental effects of endocrine disruptors: A report of the USEPA-sponsored workshop. Environ Health Perspect 104(Suppl 4), pp. 715–740

Sanchez, O. (2022). Detox before Energise: A step-by-step guide to efficiently respond to our modern environment. The hidden dangers in food, air and water, keeping you from reaching your ideal weight, damaging your health at the cellular level and reaping you from your vital energy and clouding your mind. London. Nutrunity Publishing. (available for pre-order)

Porpora, MG. et al. (2014). A promise in the treatment of endometriosis: an observational cohort study on ovarian endometrioma reduction by N-acetylcysteine. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013, 240702. doi.:10.1155/2013/240702

Schwertner, A. et al. (2013). Efficacy of melatonin in the treatment of endometriosis: A phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pain. 154(6), pp. 874-81. doi.:10.1016/j.pain.2013.02.025. Epub 2013 Mar 5. PMID: 23602498

Kong, S. et al. (2014). The complementary and alternative medicine for endometriosis: A review of utilization and mechanism. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. eCAM, 2014, 146383. doi.:10.1155/2014/146383

Burks-Wicks, C. et al. (2005). A Western primer of Chinese herbal therapy in endometriosis and infertility. Women’s Health. 1(3), pp. 447-463.